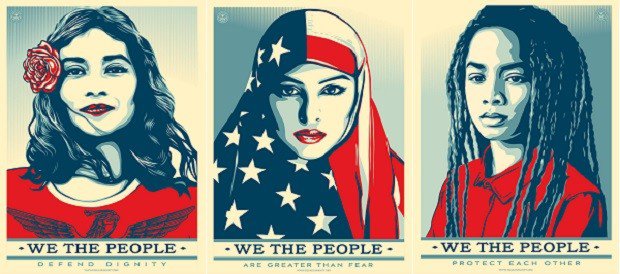

During the many protests that have been held in the first few weeks of Donald Trump’s presidency, one image has been prominent on various signs and posters. The image is a graphic representation of a photo of a young Muslim American woman, who is wearing an American flag hijab. Famed graphic artist Shepard Fairey created the image based off a photograph by NY-based artist Ridwan Adhami. The poster was part of Fairey’s “We the People” series, which features several subjects from a variety of backgrounds. These images were printed as advertisements in the Washington Post, distributed widely on inauguration day, and made available to download for free online.

Not surprisingly, these images were prominent at the Women’s March on Washington and other sister marches that occurred on the Saturday after the inauguration, but the one image of a hijabi woman was clearly the most popular image at the protests. Additionally, this image has been used more frequently, as Muslim lives were literally threatened by Trump’s disastrous attempt at banning certain immigrants from entering the US. Protestors flocked to airports across the country, many carrying signs of support for Muslim immigrants that featured this image.

Although on the surface, an image of a Muslim woman, proudly wearing an American flag, appears to be a beautiful symbol of the inclusive America that progressive activists value, it is important to critically examine the various interpretations of this image. Ultimately, this image does more positive work in society than negative work, but we need to be aware of how this image plays on loaded symbols and icons, the emotions of the viewers and the larger political context.

When examining an image like this, it is essential to understand what the subject and artist think about the significance of the image. In 2007, professional photographer Ridwan Adhami, a Muslim and Syrian American, took this picture of Munira Ahmed, a 32-year-old native of New York City, for use in a Muslim magazine. Fairey selected this photo from several similar images of Muslim women wearing American flag hijabs because he thought that Ahmed looked like a normal person.

In an interview with Slate, Ahmed explains that she doesn’t normally wear the hijab, but she thinks that the image displays the deep connection between her faith and her national identity. Ahmed states, “What’s most apparent and symbolic in the image no matter who’s looking at it is that this is a Muslim woman and an American woman and she is both of these things and she is not compromising either.” She cannot separate her identity as an American, born and raised in this country, from her religious faith.

Similarly, Fairey discusses how these images present an alternative way of being patriotic while also celebrating progressive values of inclusion and diversity. As Ashley Campbell has written about previously in this blog on our site, there are different forms of patriotism besides the absolute “love of country.” Fairey explains in an interview with PBS, “The idea was to take back a lot of this patriotic language in a way that we see is positive and progressive, and not let it be hijacked by people who want to say that the American flag or American concepts only represent one narrow way of thinking.” In other words, the conservative traditionalists do not hold claim over the label of patriotic Americans. This image is a way for Ahmed to display that she is unapologetically both American and Muslim.

On the other hand, critics of this image have brought up notable concerns about how this image can be misinterpreted and taken out of context. One concern is that this image simply reduces Muslim women like Ahmed to the symbols of the headscarf and the American flag, two highly loaded icons of larger political struggles. In an article, “I’m a Muslim Woman, Not a Prop,” Melody Moezzi writes about her frustration of seeing Muslim women reduced to a piece of fabric, the headscarf, which a majority of Muslim women don’t even wear. She explains, “Images of presumably patriotic Muslim American women turning flags into headscarves imply that we are easily identifiable by a piece of fabric, which we are not!”

She also argues that Muslim women don’t need to prove their patriotism in order to be seen as American, “Certainly, Muslim American women are no less American than our non-Muslim counterparts. But other Americans need not literally drape their heads in the flag to prove their Americanness.”

Furthermore, Joojoo Azad argues in an article that many Muslim women don’t want to wear a flag because they are critical of what the stars and stripes represent in terms of US foreign policy. Azad writes, “Know the American flag represents oppression, torture, sexual violence, slavery, patriarchy, and military & cultural hegemony for people of color around the world whose homes and families have been destroyed and drone-striked by the very person/former president whose campaign images this one seeks to replicate.”

Additionally, Melody Moezzi points to the diversity of Muslim women, which is not represented in this overly simplified image. Instead of turning Muslim women into props or icons of Islam and American patriotism, Moezzi wants Muslim women to be seen for their complexities. This is a significant critique of how both those on the right and left often use images such as this one as icons of larger political struggles while not taking into account the actual concerns of Muslim women. For instance, in the post-9/11 days, images of Afghani women wearing the burqa were used by both progressive feminists and conservative Christians to claim that the US intervention in Afghanistan would be a way to liberate the covered and presumably oppressed women.

It is important to take these critiques seriously since this image does oversimplify the complex issues that influence Muslim lives. On the other hand, the circulation of this image at protests and in progressive circles is one of the first times that an image of a Muslim woman has even been acknowledged in these spaces. Because of the racist rhetoric against Muslims and refugees within the right wing, progressives are finally considering the oppression that Muslims face because of their religion. The rhetoric around the Women’s March in DC, for instance, prominently featured Muslim women in the list of those fighting for justice. In addition, Linda Sarsour, a Muslim and Arab American activist, was one of the main organizers of the march.

While we need to be cautious of allowing this image to be reduced to an icon, the power of this image lies in the fact that it can easily convey the American and Muslim identity of the subject. Munira Ahmed uses the aesthetics and visual style of this image to claim her radical equality with other Americans. Although some Muslim women wouldn’t embrace the American flag, Ahmed employs the symbol of the flag along with the headscarf to assert that she does not need to abandon her religious convictions in order to be American.

The simplicity of this image also engages the emotions of viewers, especially emotions around what it means to be American and the injustices of how Muslims are being treated. An image like this hopefully creates feelings of connections between viewers and the subject of the image—not only Munira but also other Muslim Americans.

The simplicity of this image also engages the emotions of viewers, especially emotions around what it means to be American and the injustices of how Muslims are being treated. An image like this hopefully creates feelings of connections between viewers and the subject of the image—not only Munira but also other Muslim Americans.

Images like this one inherently over-simplify their subjects, but this is also part of the power of images. People are more able to relate to a simple image like this than reading a long feature article about an individual like Munira. The hope is that seeing this image will produce feelings of resonance in the viewers, and these feelings will lead people to gain further information through conversations and narratives. This information and in-person interactions might lead people to do political work to help improve the situations of Muslim Americans. This is work that we are already seeing happen as non-Muslims are fighting for Muslim rights.